NECK PAIN FROM AUTO ACCIDENT

Matthew J. DeGaetano, DC and Jason C. McCullough, DC

Certified in Personal Injury

Backover Crash

NECK PAIN FROM AUTO ACCIDENT

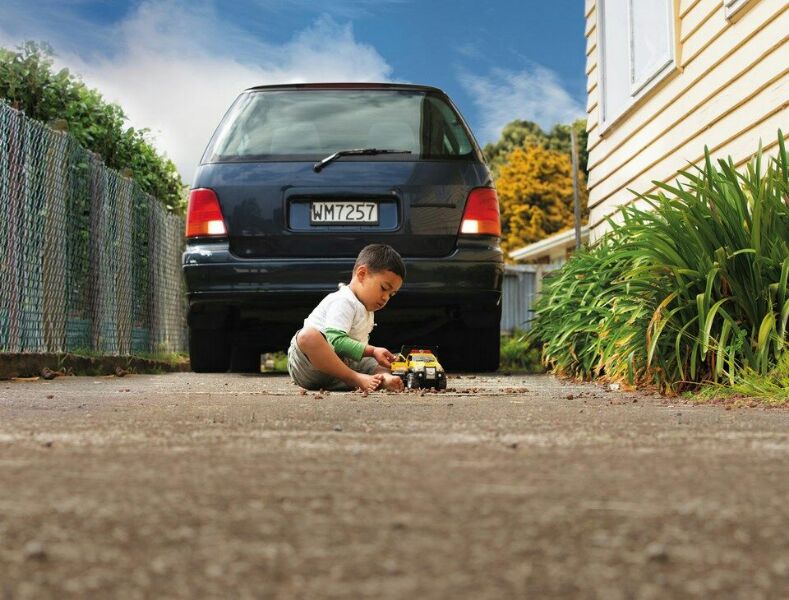

What is a backover crash?

A backover crash occurs when a vehicle backs into a person such as a pedestrian or bicyclist, often when exiting

a driveway or parking spot. These crashes typically are at low speeds. Crashes that involve multiple vehicles or

vehicles that back into objects aren’t considered backover crashes.

How widespread is the backover problem?

Government databases generally record only crashes on public roads, but most backover crashes occur in

driveways and parking lots. Until recently no federal data system collected information on all backover crashes

in the United States. An overall picture could be gleaned from a review of crash data from the National

Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), hospital emergency department records, death certificates,

and media sources. Because these sources may not capture all of the deaths and injuries, Congress directed

NHTSA to develop a database of injuries and deaths in nontraffic events involving motor vehicles. 1

In 2009, NHTSA launched the Not-in-Traffic Surveillance (NiTS) crash database of nontraffic events resulting

in injuries and deaths, which can be used to calculate a national annual estimate. Based on 2007-2011 NiTs data

and data about onraod crashes, NHTSA estimates that 267 deaths and about 15,000 injuries occur annually in

backover crashes. 2

NECK PAIN FROM AUTO ACCIDENT

Most backover incidents don’t happen on public roads. NHTSA estimates that 39 percent of backover fatalities

occur in residential spaces such as driveways and the parking lots of apartment and townhouse

complexes. 7 Nonresidential parking lots account for only 17 percent of backover fatalities, but 52 percent of

backover injuries.

Three Australian studies have looked at the circumstances surrounding the deaths of children in low-speed runover

crashes, including cases in which the vehicles were moving forward as well as reversing. A study of deaths

of children younger than 5 in 2000-10 found that 37 percent of the deaths occurred in residential driveways and

11 percent occurred on public roads. 4 A review of child deaths in driveway crashes in 1996-98 showed 86

percent of the drivers were members of the struck child’s family or family friends. 8 A study in Queensland

found that parents were driving in 11 of the 15 low-speed run-over fatalities of children that occurred in the

state in 2004-08. 9

What types of vehicles are most often involved?

An analysis of driveway backovers involving children in Utah in 1998-2003 found that children were more

likely to be injured by a pickup truck, minivan or SUV than a car, relative to the number of registered vehicles

of each type, although the difference between SUVs and cars was not significant. 10 Larger vehicles like SUVs

and pickup trucks typically have bigger blind zones than cars, 11, 12 in large part because they sit higher off the

ground, making it more difficult for drivers to see children and smaller objects near the rear of the

vehicle. Consumer Reports measures distances behind the rear of a vehicle that a driver cannot see and has

found that a 5-foot-8-inch-tall driver in an average midsize SUV can see up to 18 feet behind the vehicle,

compared with 13 feet for an average midsize sedan. 13NHTSA measurements of rear visibility also have found

that blind zones for shorter drivers are typically much bigger.

Technology may never be 100 percent effective so drivers will always need to be vigilant. The national “Spot

the Tot” campaign, developed by Safe Kids Utah, encourages drivers to walk completely around a vehicle

before getting in and to roll down windows to hear what is happening near the vehicle before backing. 21 It also

suggests teaching children to move away from a vehicle when started and to have them stand in full view of the

driver when backing. An Australian review of crashes in which children were run over at low speeds found that

more than three-quarters of drivers were unaware that a child was in the immediate vicinity of the vehicle at the

time the crash occurred. 4

Separating children’s play areas from driveways also may help. A study in New Zealand in the 1990s found that

children in homes without a fence separating the driveway from the play area were 3½ times more likely to be

killed or injured in a driveway crash. 22

NECK PAIN FROM AUTO ACCIDENT

References

NECK PAIN FROM AUTO ACCIDENT

1 U.S. House of Representatives. H.R. 1216: Cameron Gulbransen Kids Transportation Safety Act of 2007.

Washington, DC: US Congress.

2 National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. 2014. Backover Crash Avoidance Technologies FMVSS No.

111: Final Regulatory Impact Anlysis. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation.

3 Nhan, C.; Rothman, L.; Slater, M.; Howard, A. 2009. Back-over collisions in child pedestrians from the

Canadian hospitals injury reporting and prevention program. Traffic and Injury Prevention 10(4):350-3.

4 Anthikkat, A.P.; Page, A.; and Barker, R. 2013. Low-speed vehicle run over fatalities in Australian children aged

0-5 years. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 49(5):388-93.

5 Anthikkat, A.P.; Page, A.; and Barker, R. 2013. Risk factors associated with injury and mortality from paediatric

low speed vehicle incidents: a systematic review. International Journal of Pediatrics 2013.

6 Griffin, B.R.; Watt, K.; Shields, L.E.; and Kimble, R.M. 2014. Characteristics of low-speed vehicle run-over

events in children: an 11-year review. Injury Prevention. Advance online publication doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2013-040932.

7 National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. 2008. Fatalities and injuries in motor vehicle backing crashes:

Report to Congress. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation.

8 Nee, T.; Wylie, J.; Attewell, R.; Glase, K.; and Wallace. A. 2002. Driveway deaths: fatalities of young children

in Australia as a result of low-speed motor vehicle impacts. Road Safety Report no. CR208. Canberra, ACT: Australian

Transport Safety Bureau.

9 Griffin, B.; Watt, K.; Wallis, B.; Shields, L.; and Kimble, R. 2011. Paediatric low speed vehicle run-over

fatalities in Queensland. Injury Prevention 17(Supplement):i10-3.

10 Pinkney, K.; Smith, A.; Mann, N.; Mower, G.; Davis, A.; and Dean, J. 2006. Risk of pediatric back-over injuries

in residential driveways by vehicle type. Pediatric Emergency Care 6:402-407.

11 Mazzae, E.N. and Garrott, W.R. 2008. Light vehicle rear visibility assessment. Report no. DOT HS-810-909.

Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

12 Mazzae, E.N. and Barickman, F. 2009. Direct rear visibility of passenger cars: Laser-based measurement

development and findings for late model vehicles. Report no. DOT HS-811-174. Washington, DC: National Highway

Traffic Safety Administration.

13 Consumer Reports. 2012. Best and worst rear blind zones.

Available: https://www.consumerreports.org/cro/2012/03/the-danger-of-blind-zones/index.htm. Accessed: August 4, 2012.

14 Office of the Federal Register. 2014. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration – Final rule. Docket no.

NHTSA-2010-0162; 49 CFR Part 571 Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards; Rear Visibility. Washington, DC: National

Archives and Records Administration.

15 Highway Loss Data Institute. 2013. HLDI facts and figures: 1981-2014 vehicle fleet. Vehicle Information

Report VIF-13.

NECK PAIN FROM AUTO ACCIDENT

16 National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. 2006. Vehicle backover avoidance technology study: Report

to Congress. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

17 Kidd, D.G. and Brethwaite, A. 2014. Visibility of children behind 2010-2013 model year passenger vehicles

using glances, mirrors, and backup cameras and parking sensors. Accident Analysis and Prevention 66:158-67.

18 Insurance Institute for Highway Safety. 2011. Comment to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration

concerning proposed amendments to rearview mirrors safety standard. Docket no. NHTSA-2010-0162. January 31, 2011.

Arlington, VA.

NECK PAIN FROM AUTO ACCIDENT

19 Kidd, D.G.; Hagoski, B.L.; Tucker, T.G.; and Chiang, D.P. 2014. Effects of a rearview camera, parking sensor

system, and the technologies combined on preventing a collision with an unexpected stationary or moving object. Arlington,

VA: Insurance Institute for Highway Safety.

20 Llaneras, R.; Neurauter, M.; and Reen, C. 2011. Factors moderating the effectiveness of rear vision systems:

what performance-shaping factors contribute to unexpected in-path obstacles when backing? SAE 2011 World Congress &

Exhibition Paper no. 2011-01-0549. Warrendale, PA: Society of Automotive Engineers.

21 Intermountain Primary Children’s Medical Center. 2014. Spot the tot brochure.

Availabile:https://intermountainhealthcare.org/hospitals/primarychildrens/Documents/SPOT_TOT_Info_Card_opt.pdf.

Accessed: March 28, 2014.

22 Roberts, I.; Norton, R.; and Jackson, R. 1995. Driveway-related child pedestrian injuries: a case-control

study. Pediatrics 95:405-408.

NECK PAIN FROM AUTO ACCIDENT